Perpetual Daydream or the paradoxical state of a society at the threshold of a spectacle besiege

The Glamor of Consumption: Unveiling Capitalism's Grip on Urban Life and Architecture

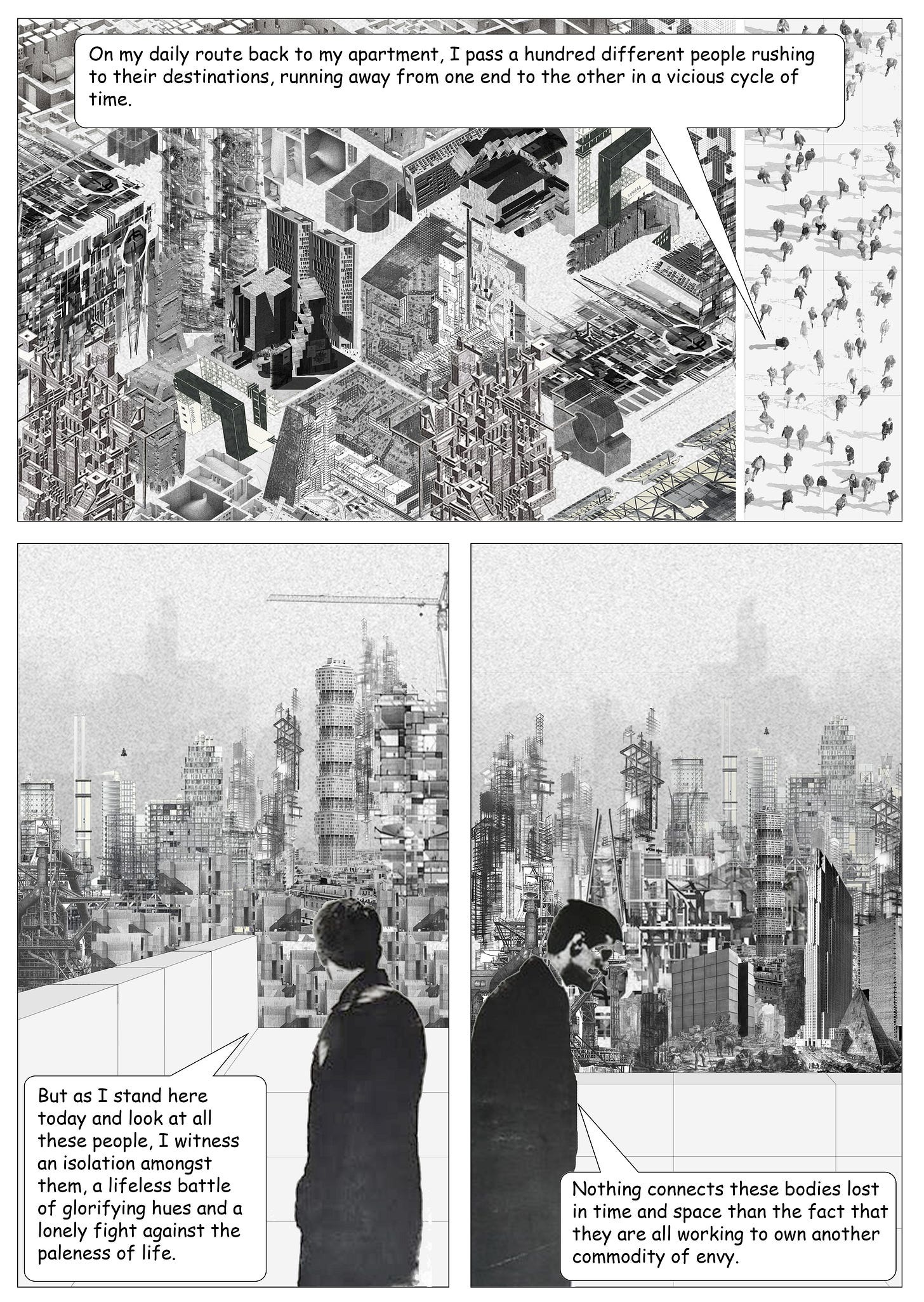

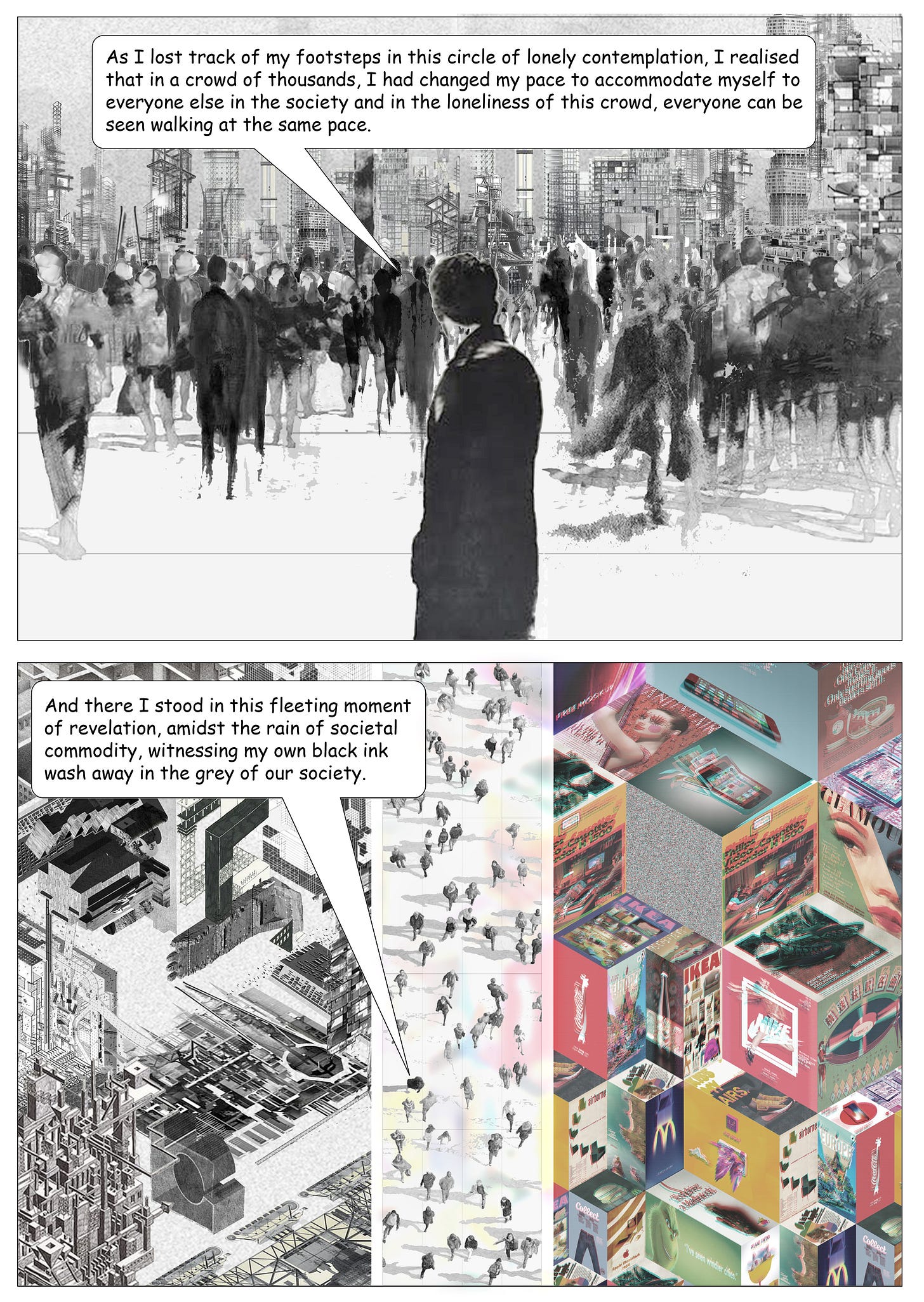

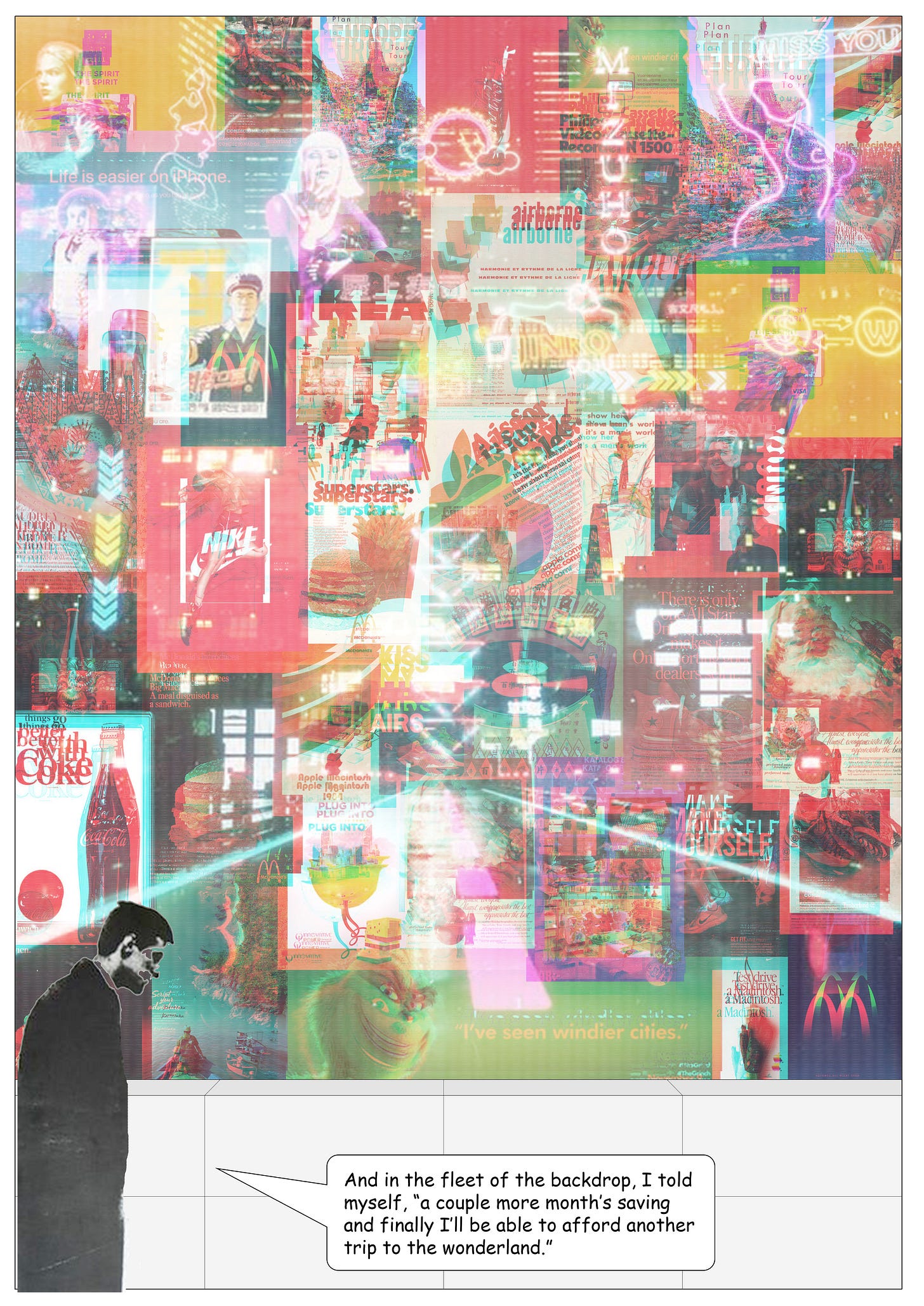

As we navigate the urban landscape, countless images flood our vision, each carrying its own visual message. History has shown us how this saturation of imagery is deeply tied to the rise of consumer culture. The towering billboards and glowing neon signs that dominate capitalist cities perpetually offer a vision of a glamorous future. These images subtly suggest that transformation—whether personal or social—can only be achieved through consumption. In other words, to desire the lives of others, we must first spend more, reinforcing the relentless cycle of envy and materialism.

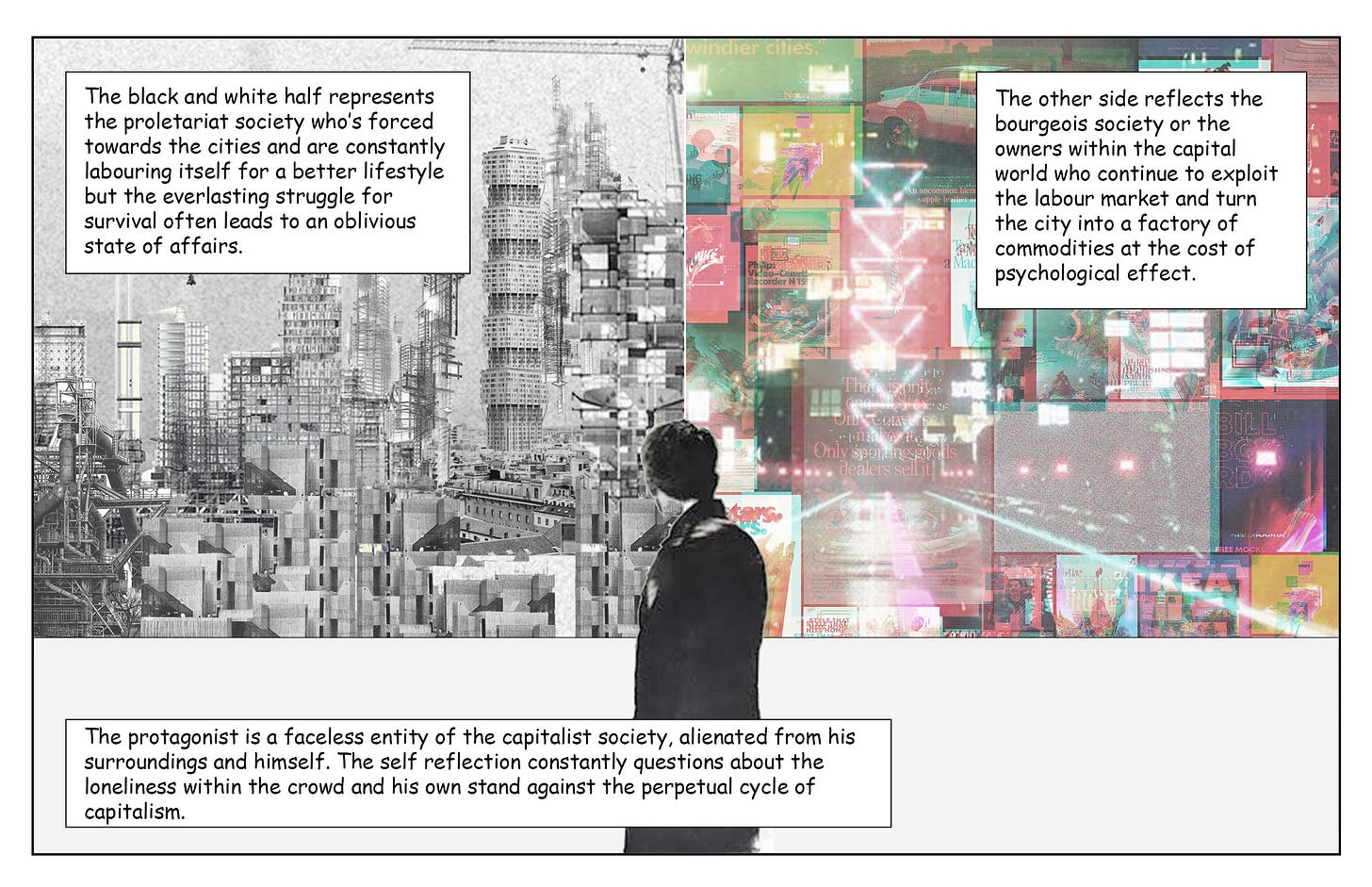

The culture of the publicity image has long woven its way through societies, embedding itself as a powerful force shaping people's lives. With capitalism flourishing on the back of abundant labor, this culture has amplified social inequalities, dividing society into distinct classes: the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. The persistent inequalities born from this system compel us to confront the deeper, structural issues that are often masked by the allure of temporary pleasure and envy. These images act as blindfolds, distracting us from the long-term, inescapable consequences of a system built on disparity.

The psychological interplay of envy and glamor draws us into the depths of the urban experience, where an overwhelming flood of information inundates the senses, and the constant noise of the city drowns out meaningful connection. In this chaotic environment, the so-called free society becomes increasingly alienated, as individuals retreat into isolation, surrendering themselves to the allure of commodities. Human lives, once yearning for genuine connection, now seek solace in the acquisition of yet another product—a hollow substitute for the human touch, offered by a capital-driven society.

In a so-called 'free society,' where the tension between who a person is and who they aspire to be perpetually exists, a two-fold dilemma emerges: should one submit to the forces of capitalist exploitation, or become fully conscious of its roots and take a stand against it? This existential question prompts deep self-reflection, particularly for architects. What is their role amid the social anesthesia that permeates society? As we acknowledge that architecture has largely become a tool of capital, we must ask ourselves: do we exploit this structural hierarchy to serve the bourgeoisie, or do we remain steadfast in the belief that architecture, at its core, must serve society as a whole—including the proletariat?