The Strength of Weakness

Exploring the Evolution of 'Weak Architecture' as a Response to Modernism's Rigid Legacy

By the end of the 20th century, modernist architects increasingly viewed themselves as the sole agents capable of cleansing the world through their designs - aiming to impose utopian ideas on the built environment - solutions they believed to be permanent fixes for urban and social issues. Modernists, in pursuit of universality, created designs that sought to portray a singular, overarching vision, imposing rigid spatial solutions. This pursuit rendered the movement hedonistic in nature - rigid, lifeless, and detached from the everyday experience of lived experience.

Emerging from the ideals of the Enlightenment, Modernism grew in prominence, characterized by strict geometric forms and rigid principles that defined architecture in absolute terms. Some architects conceptualized their buildings as “machines for living,” while others devised a set of rules to guide their precise straight lines. This adherence to monumentality and rigor resulted in what was often referred to as “strong architecture” - an architectural style dominated by grand, monumental, imposing buildings that commanded space.

At the heart of modernism, however, lay a growing issue: the isolation and alienation that these designs inadvertently fostered. The architectural image became a reflection of the societal disconnection, revealing the limitations of Modernist vision. The Modern problem, then, was not merely aesthetic but deeply existential, creating spaces that were provisional and estranged from the human experience they meant to serve.

As Einstein famously stated, "with every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction." In response to the dominance of strong, rigid modernist architecture, Ignasi de Solà-Morales introduced a counterpoint in the form of "Weak Architecture"—a Post-modernist remedy.

Intertwining his own interpretation of meaning, de Solà-Morales crafted a vocabulary filled with contradictions, yet imbued with purpose and from the outset, "Weak Architecture" stood in deliberate opposition to the strength that modernists so highly prized.

Ignasi De Sola Morales saw “an architectonic proposition whose aim is to go deep… can't find support in a fixed image, can't follow a linear evolution… each design must catch with the utmost rigor, a precise moment of a flittering image in all its shade.” In other words, he saw architecture not as a fixed monument, but as something far more fluid, responsive to the uncertainties of life.

By embracing the fragile, the transient, and the provisional allowed the buildings to breathe, to adapt, and to evolve alongside the people who inhabited them.

Weak architecture did not impose itself on space but rather coexisted with it - an architecture that whispered to its inhabitants rather than shouted. It acknowledged that life is messy, unpredictable, and full of change. It invited ambiguity and welcomed the idea that a building could be incomplete, always in the progress of becoming, never fully resolved.

In a world where Modernism sought permanence, Weak Architecture celebrated the temporality, the ephemerality, and the fleeting moments that give life meaning. It was an architecture that understood that the strength of a space isn’t always in its structure, but in its ability to foster connection, to remain open to interpretation, and to offer a solace in its quiet.

Let us take a deeper, introspection at the idea of “Weak Architecture” from the philosophies of profound thinkers and relate it back to its principle notion to understand it better.

The “Idea” of Weakness - Deleuze’s theory on “Becoming”

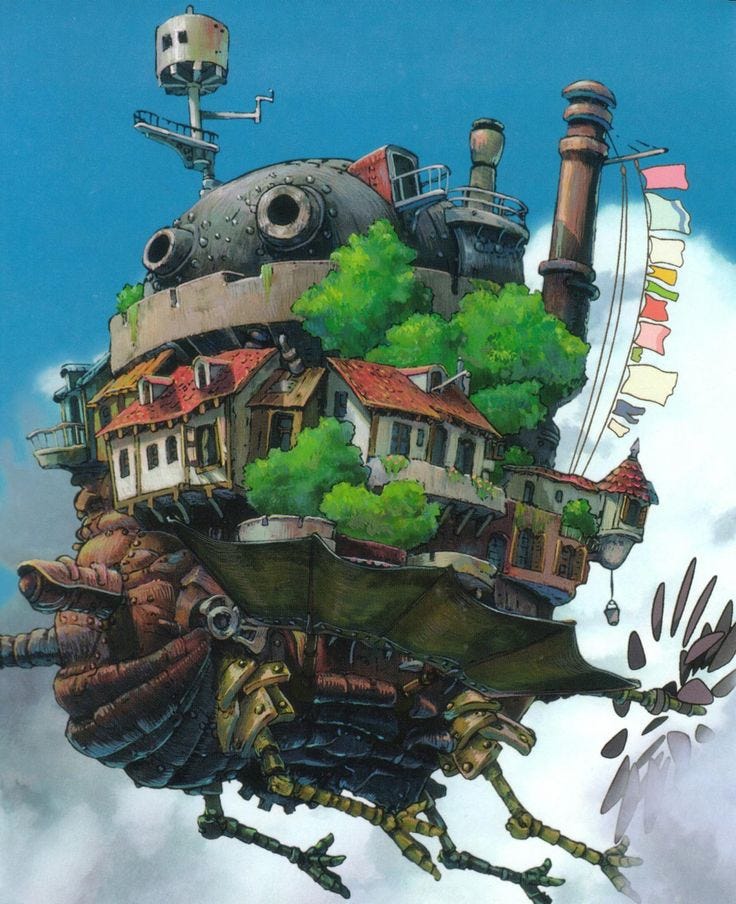

In revisiting the concept of The Ship of Theseus from a previous blog, Gilles Deleuze’s theory of "Becoming" comes to mind. Deleuze understood identity not merely as a transition from one state to another, but as a dynamic, ever-changing process. To him, identity was a verb—always in flux. Ontologically, Deleuze argued that identity is a continuous process of becoming, constantly evolving in response to both internal conflicts and external influences. Rather than adhering to a fixed definition that implies a “closed cycle,” Deleuze saw identity as an ongoing narrative we rewrite, reflecting the complexity and richness of existence.

This idea parallels the concept of “Weak Architecture,” which resists totality or the imposition of a final, unchangeable form. Instead of creating monumental structures that dictate how space should be used, weak architecture embraces temporality and ephemerality, allowing for personal interpretation and flexibility in how spaces are experienced.

De Sola Morales, in his principle and practice, advocates for architecture that is sensitive to the shifting nature of contemporary urban life. By designing spaces that are open to change over time, he emphasizes multiplicity—a foundational approach where spaces are not fixed but have the potential to evolve as urban life itself evolves. Architecture, in this view, is not an endpoint but an ongoing engagement with reality.

A key aspect of this approach is its departure from the “closed loop” of fixed identity. Without a definitive endpoint in the use or function of a space, the cycle remains open. Sola Morales reflects on Nietzsche’s proclamation that "God is dead," aligning it with his own belief in the necessity of keeping architecture open-ended. He writes, "the disappearance of any kind of absolute reference to close the system of our knowledge and our values at the point at which we articulate these in a global vision of reality."

“To define is to limit”— echoes through the principles of weak architecture, which strives for multiplicity, adaptability, and openness to new interpretations. By resisting rigid definitions, architecture, like identity, remains in a state of becoming.

The Rosebud “Event” - An Analogy on Weak Architecture

Recently, I re-watched one of my favorite mid-twentieth-century films, Citizen Kane. The protagonist's final word, "Rosebud," struck me with an intriguing analogy. The entire film revolves around this mysterious word, as multiple characters try to decipher its meaning. While "Rosebud" ultimately refers to a personal memory from the protagonist’s life, its significance lies in the "event" that surrounds the word, rather than the word itself.

Through the lens of Sola-Morales, "Rosebud" can be seen as an "event" where meaning remains fluid and elusive, resisting the dominant narrative of power and control. To the protagonist, "Rosebud" symbolizes a yearning for a simpler, more authentic past. To others, however, it remains an enigma, devoid of power or value beyond its emotional resonance for one person.

This analogy sheds light on a key concept in understanding "Weak Architecture"—the idea of an "event." An event, in this context, disrupts, transforms, or gives meaning to architectural spaces through human interaction, temporal change, and contingency. It represents the unpredictable and transient forces that shape architectural spaces over time. Instead of focusing solely on the objectivity and permanence of architectural forms, Sola-Morales emphasizes how spaces are continuously redefined by events—whether through daily use, historical occurrences, or social shifts.

To delve deeper, we must ask: how do events leave a lasting mark on the identity of both human beings and architectural spaces? How do these events influence the process of "becoming" that we discussed in the previous section? Moreover, is there a psychological impact that causes us to evolve in a non-linear way due to these transformative events?

The “Poetics” of Weakness - Bachelard and the Intimate Meaning of Space

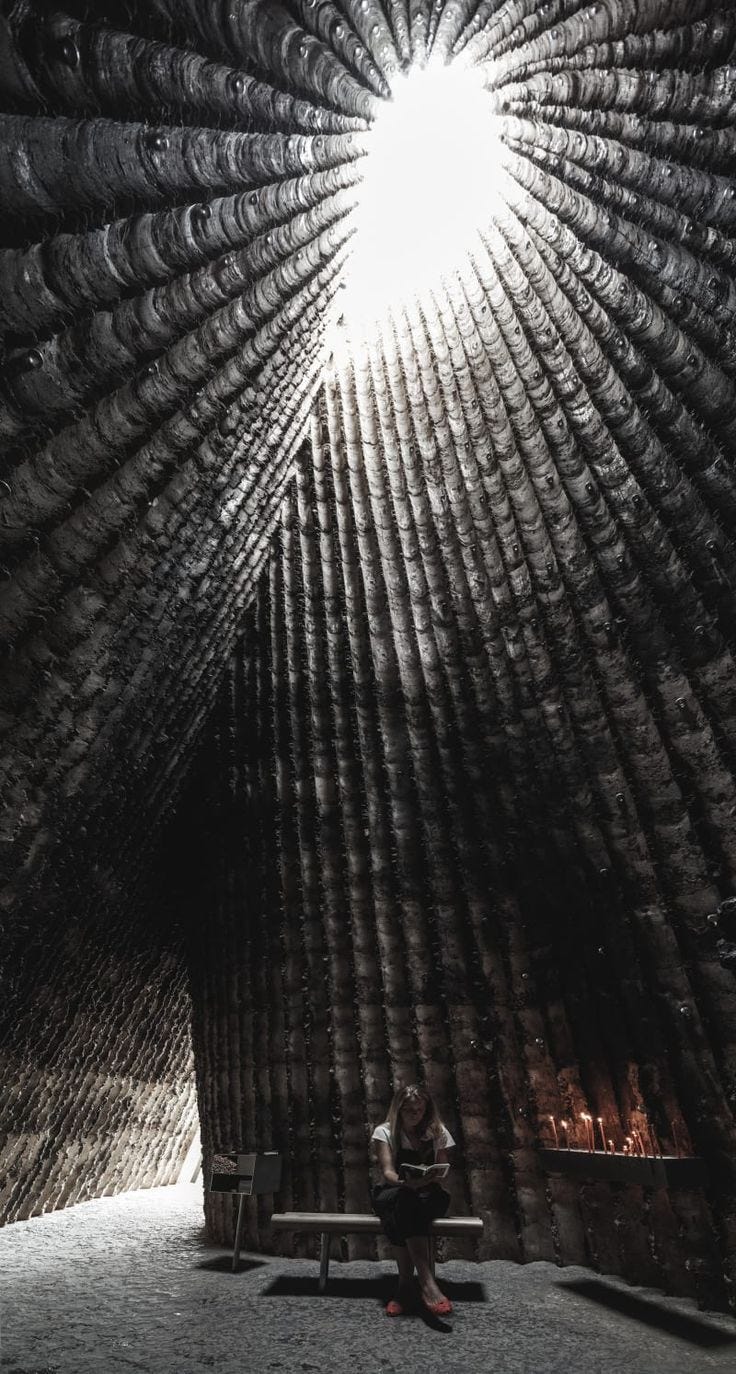

Events play a pivotal role in mediating the relationship between people and space. As the human body navigates various environments, events—whether fleeting or significant—become the bridge connecting space to lived experience. In The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard provides a poetic perspective on this interaction, suggesting that space is not a static entity but a vessel that holds personal memories and dreams.

Both Sola-Morales and Bachelard argue that architecture and space transcend their physical forms. For them, space is dynamic, continuously shaped by human interaction, memory, and imagination. Sola-Morales focuses on the external forces that influence architecture, while Bachelard explores the internal, emotional desires that inform how we perceive space. Together, their ideas deepen our understanding of "Weak Architecture"—architecture that is fluid, open, and dependent on human presence and experience, rather than being monumental or fixed.

In this context, an event becomes more than a mere moment in time; it is an ongoing experience that reshapes both the person and the space they inhabit. Traces of these events—wear on a wooden table, scratches on glass, dents in metal—are physical markers that show how space evolves alongside the people who pass through it. Bachelard’s Poetics of Space highlights how even the most ordinary spaces can carry deep psychological resonance, while Sola-Morales points to the impact of external events on the collective experience of architecture. Despite their different approaches, both thinkers converge on the idea that the essence of space lies in its capacity to evolve through events.

In Weak Architecture, events become the constantly shifting interaction between people and the spaces they occupy. Every encounter subtly reshapes the space, entwining it with memories, emotions, and imagination. Bachelard views space through a lens of intimacy, where even the smallest personal moments leave a lasting impression, turning mundane environments into places rich with meaning.

For both Sola-Morales and Bachelard, space is not solely defined by its material form but by the way it is lived. Ordinary, everyday environments hold the potential for transformative events, and it is these personal or collective moments that imbue them with significance. The temporal nature of events breathes life into space, as fleeting moments accumulate to form a palimpsest of memories and dreams. Through this process, architecture becomes a living entity, activated and completed by the experiences that unfold within it.

Importantly, they find the power of the event not in grand, monumental structures, but in the everyday, overlooked spaces where life quietly happens. It is these unassuming environments that are transformed into meaningful, poetic, or even politically charged sites through events.

Weak architecture, in this sense, challenges us to reconsider how we engage with the spaces around us, revealing the subtle yet profound ways in which space and experience shape one another.

“Complexity” and “Contradiction” of Weakness – Venturi’s Postmodern Rejection of Formalism

“I like elements which are hybrid rather than pure, compromising rather than clean, distorted rather than straightforward, ambiguous rather than articulated, perverse as well as impersonal, boring as well as interesting, conventional rather than designed, accommodating rather than excluding, redundant rather than simple, vestigial as well as innovating, inconsistent and equivocal rather than direct and clear. I am for the messy vitaly over obvious unity.”

- Robert Venturi

Robert Venturi in his seminal manifesto of Postmodernist architecture, called for a break away from Mies van der Rohe’s famous dictum, “Less is More”. His call for action was against the minimalist, reductive approach of the modernist architecture which aimed to provide a universal design and unintentionally devoid of human beings' consideration of dwelling in the space. Venturi, instead proposed that architecture should be left open to interpretation by embracing complexity, richness, and contradiction of spaces. He argued for an architecture that embraces its juxtaposition and contradictory design elements to create a multifractal subjective interpretation of the space.

Proposed around the same time frame as Weak Architecture, both Venturi and Sola Morales advocated for a more flexible, layered, and inclusive approach to design, but they did so from different angles. With Venturi focusing on richness in architectural forms and Sola Morales addressing the relationship between architecture and its context, particularly in a fragmented, postmodern world.

Venturi stated, “By embracing contradiction as well as complexity, I am for richness of meaning rather than clarity of meaning, for the implicit function as well as the explicit function.” For him, a valid architecture must evoke many levels of meanings, personal and collective, to create a space that becomes readable and workable in several ways at once. Rather than asking for a clear, defining use of space, he advocated to design the space that would embrace in its pure form all the meanings that overlapped with its ambiguity.

Weak Architecture, as articulated by Ignasi de Solà-Morales, embraces complexity and contradiction not as flaws but as essential characteristics of design. In the same way that Robert Venturi saw contradiction as a source of richness, Weak Architecture finds strength in its capacity to hold multiple, seemingly opposing forces together within a single space. It does not aim for a singular, dominant narrative but rather welcomes the coexistence of old and new, public and private, permanent and ephemeral elements. These contradictions create spaces that are open to interpretation and can adapt to various contexts over time, allowing for a deeper, more personal engagement with the architecture.

For Solà-Morales, the strength of Weak Architecture lies in its ability to resist rigidity and allow for fluidity. Rather than dictating how space should be used, it offers a framework that can evolve, accommodating the changing needs of its users. This approach mirrors Venturi’s idea that architecture should not be reduced to a clear, defining function, but should instead embrace ambiguity and multiplicity. Weakness, in this context, becomes a form of strength, as it provides the flexibility needed for buildings to remain relevant in an ever-changing world.

Solà-Morales often spoke of "strong" and "weak" in architectural vocabulary, where strong architecture asserts a fixed meaning, imposing a clear hierarchy and rigid order. In contrast, weak architecture thrives on openness and fluidity, its strength coming from its adaptability. By embracing the contradictions inherent in the weak/strong duality, Weak Architecture creates spaces that are not about control but about possibility—spaces where complexity is not resolved but maintained, allowing for a more nuanced and multifaceted experience. This is architecture that speaks not in absolutes but in layers, drawing power from its ability to reflect the contradictory and complex nature of contemporary life.

Weak Architecture as a Reflection of the Contemporary Condition

In today’s world, where cities and buildings are constantly evolving due to social, political, and environmental factors, weak architecture offers a radical alternative to permanence and control. It reflects the uncertainties of our time—climate change, political instability, technological disruption—by embracing flexibility and open-endedness. Weak architecture does not pretend to offer solutions; instead, it provides spaces that can adapt, evolve, and remain meaningful in unpredictable futures.

By resisting the urge to define a space once and for all, weak architecture encourages us to rethink the purpose of buildings in our lives. Are they merely functional, or do they shape our emotional and psychological experiences? Do they assert power, or do they allow us to find our own meaning? Weak architecture, influenced by Deleuze, Bachelard, and Venturi, teaches us that true strength lies in vulnerability, complexity, and the potential for transformation.

In a world where strength is often equated with dominance, weak architecture offers a poetic alternative. It values the delicate, the flexible, and the evolving over the rigid and permanent. Through the lens of Deleuze’s becoming, Bachelard’s poetics, and Venturi’s complexity, we see that architecture’s greatest potential may lie not in its ability to assert control but in its willingness to let go. Weak architecture, far from being a passive or lesser approach, invites us to experience space in a richer, more meaningful way—one that reflects the fluidity of life itself.

...to create spaces that are adaptable, human, and alive.

And there you have it—weakness isn’t always about fragility, but about flexibility, openness, and the ability to adapt to change. If you're as fascinated by how architecture reflects and influences our lives as I am, you’re in the right place. I dive into thought-provoking topics like this regularly on Preritect, exploring the intersection of architecture, philosophy, and societal change.

Don't miss out—hit subscribe to stay in the loop and keep the conversation going! Let's build something great together.